If we can come together to meet the biggest challenges in medical biology, so too we can come together to meet the challenge of climate physics.

The human race has thrived during an eleven thousand year era of extraordinary climate stability, known as the Holocene.

Now that stability is shattering. We’ve created a new era, the Anthropocene, in which our earth’s climate is driven not solely by the geological rhythms of nature, but also by the frenzied activity of humans.

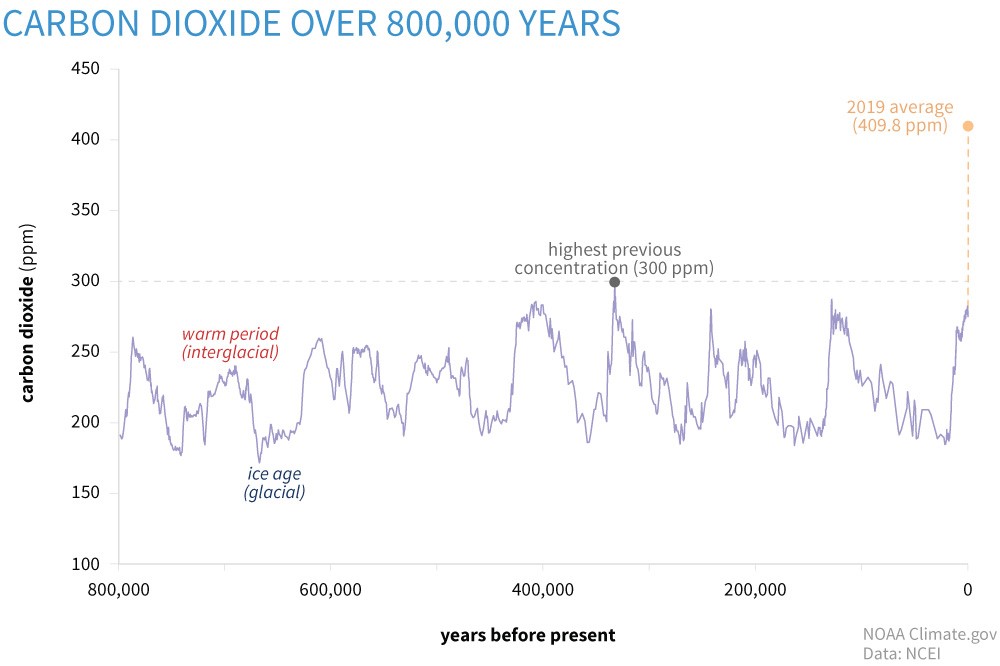

As the Industrial Revolution spread, the earth’s climate began to change. Since the publication of Smith’s Wealth of Nations, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen to its highest levels in over 800,000 years. Our planet’s average temperature is already 1 degree Celsius warmer. In fact, the last five years have been the warmest on record.

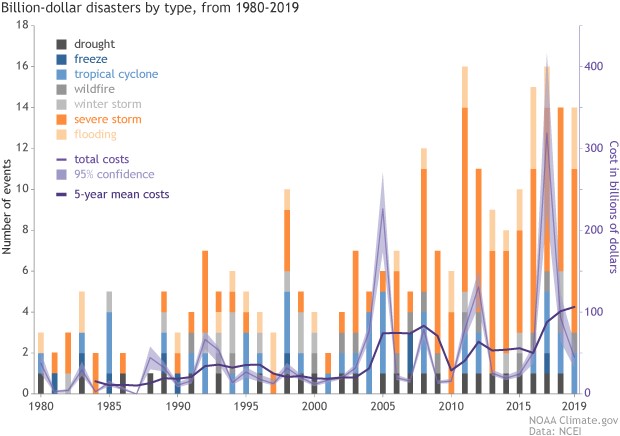

The impacts on our planet’s finely tuned ecosystems are intensified. Our oceans have become 30 percent more acidic since the Industrial Revolution. Sea levels have risen 20 centimetres over the past century, with the rate of increase doubling in the past two decades. The pace of ice loss in the Arctic and Antarctic has tripled over the last decade. Extreme climate events, hurricanes, wildfires, and flash flooding are multiplying. What had been Biblical is becoming commonplace.

These effects began to eliminate individual species and are now destroying entire habitats. Scientists estimate that there have been five mass extinctions in the history of our planet, but human activity is now driving the sixth, with extinction rates 100 times the average of the past several million years. Over my lifetime, the population of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians is estimated to have fallen by 70 percent.

Perhaps because they were not financially valued, these losses were initially downplayed, and their cause was treated as an issue for another day. But now the effects of climate change are beginning to affect assets, which have a market price, making the scale of the looming calamity more tangible.

And now with the COVID crisis exposing the tragic folly of undervaluing resilience, and ignoring systematic risk, society is beginning to place greater value on sustainability, and that is a pre-condition to solving the climate crisis.

So, What Needs To Be Done?

We must first understand the causes of the climate crisis.

Scientists have concluded that the pace of global warming is roughly proportional to the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. And that means we have a carbon budget, the remaining amount of carbon dioxide and other gases that can still be released before our climate becomes even more volatile and destructive.

To stabilise temperature rises at any level, we must reach net zero, where the amount of carbon emitted and the amount taken out of the atmosphere, are equal. So, it is important to recognise that net zero isn’t a slogan, it’s an imperative of climate physics.

Thus far, efforts to address climate change have struggled between urgency and complacency. The urgency of carbon budgets that could be consumed within a decade and the complacency of continuing to add new committed carbon in our new cars, homes, machines and power plants.

The urgency of the looming mass extinction, the complacency of not valuing the loss of individual species and the destruction of entire habitats. The urgency to re-orient the financial system for the massive investment needed to create a sustainable economy, yet the complacency of many in finance, who don’t know their own carbon budgets despite asking others to achieve net zero.

These tensions reflect the common challenges of value that we’ve seen in previous lectures, namely human frailties, market failures, and the flattening of values.

Human frailties create a tragedy of the horizon. That means the catastrophic impacts of climate change will fall largely on future generations. The current generation with our horizon fixated on the current news, business and political cycles, has few direct incentives to solve the issue, even though the sooner we act, the less costly it will be.

Market failures create the tragedy of the commons, and this arises when individuals acting in their own self-interest, undermine the common good by depleting a shared resource, such as the ongoing deforestation of the Amazon.

The solution lies in pollution pricing.

It is essential, but so far carbon prices, that is, taxes on carbon emissions, have been applied only sparingly. They are also set far too low, averaging $3 per tonne globally, well short of the estimated $75 level needed by the end of this decade, to get us on track towards net zero.

And while it is effective to assign a monetary value to a scarce resource, you might well ask why companies stay knowingly on a path inconsistent with net zero goals.

Again this points to the flattening of values. We’ve been trading the planet off against profit, living for today and leaving it to others to pay tomorrow.

There is a way out

The Nobel economist, Elinor Ostrom, has documented how a community can cooperate to manage a scarce resource. And this is exactly what this year’s COP26 Glasgow summit is about.

It’s about bringing companies, communities and countries together to manage our global ecosystem by developing a consensus for sustainability.

If we can unleash the dynamism of the private sector to put value in the service of values, and if society sets a clear goal, it will become profitable to be part of the solution, and costly to remain part of the problem.

If, as it is beginning to appear, society’s values are being redefined, prioritising resilience, solidarity and sustainability, the tensions between urgency and complacency can be resolved.

The challenge of shifting our economies to net zero is an enormous opportunity, and it’s one that will have to involve every company in every sector in every country.

Building a sustainable future will be capital-intensive after a long period when there has been too little investment.

It will be job-heavy when unemployment is soaring. It will be global when we are being pulled to the local.

To seize this opportunity and solve the climate crisis, we must address three challenges, engineering, political, and financial. All are within our grasp.

We need to electrify everything and turn electricity generation green. Existing technologies, when applied at scale, can economically reduce about 60 percent of emissions, keeping the world on track to net zero consistent with 1 and a half degrees warming.

However, we don’t yet have commercial technology to cut around 25 percent of man-made greenhouse gas emissions. We need greater investment and innovation in critical technologies, such as hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, and sustainable aviation fuels.

These challenges disguise enormous opportunities. In all cases, speed and scale will be critical, and that is why someone like Bill Gates is leading a multibillion-dollar breakthrough energy fund, to help drive these technologies to competitive scale, in short order.

The more credible our governments’ commitment to net zero is, the more investors will pour money in, and the more a virtuous circle of large scale and greater efficiency will operate.

We need a strong consensus to break the tragedies of the horizon and the commons. So far, over 126 countries have set net zero targets, and subnational governments are making pledges and enacting plans. Increasingly industrial groups and financial institutions are beginning to commit to do their part.

Greater consumer demand for sustainable products increased the economic returns to green technologies and the political returns to green policies, and this is how a path to a more sustainable world begins to appear.

In this context, finance can play a decisive role. The more the financial sector focusses on the transition to net zero, the more new technologies will be financed.

Investors will be able to track whether their investments are consistent with their values, and if not, the easier it will be to move those savings somewhere else. Sustainable investing can shift from the fringes to the mainstream, driving the transformation. This is how values drive value.

And that is why our objective for COP 26 is to put in place the foundation for every financial decision to take climate change into account. A financial system in which climate change is as much a determinant of a company’s value as changes in credit worthiness or interest rates or technology, so that value reflects values.

To bring climate risks and opportunities into the heart of financial decision-making requires three Rs: reporting, risk and returns.

These lectures have argued that a common cause of the three crises of Credit, Climate and COVID is how we measure value. Indeed, past crises have usually forced improvements on how we measure the impacts of companies and the risks that they face.

Since what gets measured gets managed, every major company should disclose how climate change affects its current business and how it could affect their strategies. Large companies should also develop and disclose their plans to move to net zero.

Now the gold standard for this reporting has been created by something called the TCFD (the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures), which is a private sector standard now backed by financial institutions, controlling 150 trillion dollars of assets.

That sounds like a lot and it is a lot and now is the time for the G20 to make the TCFD mandatory for all large companies. In November 2020 the UK Government announced its intention to make TCFD-aligned disclosures mandatory across the economy by 2025, with a significant portion of mandatory requirements in place by 2023.

Secondly, climate risk management must be transformed. Climate risks are different from conventional financial risks because they are unprecedented, so the past isn’t a good predictor of the future.

As climate risks will ultimately affect every sector of the economy, the financial system cannot diversify out of them.

Banks and insurers must help break the tragedy of the horizon by understanding the carbon emissions that they are financing, developing strategies for managing them down, and disclosing their plans to align with the transition to net zero. Now seventy central banks from countries responsible for three quarters of the world’s emissions are working to help make this happen.

Thirdly, on returns. Addressing climate change is ultimately about delivering what society values. We need to mobilise mainstream finance to help all companies get on track to net zero.

Today, investors have a say on pay for executive pay packets, but they should also have a say on transition, specifically a vote on whether a company is taking the necessary steps to transition to a net zero world. This would embed a critical link between responsibility and accountability.

Investors too should disclose how closely their portfolios are aligned with the transition. Current calculations suggest the financial system as a whole is funding temperature increases of over three degrees centigrade. That is a striking gap between what society wants and what the market values.

But exposing this gap should help close it.

The more investors help portfolio companies and assets move towards net zero, the more they will reinforce the emerging engineering and political momentum.

It is important to recognise that a whole economy transition isn’t only about funding deep green activities or blacklisting dark brown ones.

We need fifty shades of green to catalyse and support all companies moving towards net zero. To conserve our carbon budget, companies will seek to meet their net zero targets through an appropriate mix of emission reductions and credible carbon offsets, including nature-based solutions, such as reforestation and the switch from brown to green power.

To unlock that market, a new private sector taskforce is working to create this critical market in time for the COP26 Glasgow summit.

Ultimately, the private sector needs effective public policies. These include tax and spending measures, such as carbon prices and targeted investments in emerging sectors, and it also means new rules, including mandates for clean fuels and greater energy efficiency. A critical point is that the more credible and predictable climate policies are, the more the financial system will anticipate future measures, and encourage companies to start adjusting today.

The solutions to the climate crisis are intimately tied to our fiscal, economic and social wellbeing.

We will not get to net zero without innovation, investment and profit. Continued growth is not a fairy tale, it is a necessity.

A market in the transition to net zero is now being built on these foundations of reporting risk management and returns. It is funding the initiatives and innovations of the private sector and it can amplify the effectiveness of climate policies of governments and accelerate the transition to that low carbon economy.

It is turning an existential risk into one of the greatest commercial opportunities of our time.

It is now within our grasp to create a virtuous cycle of innovation and investment for the net zero world that people are demanding, and that future generations deserve. In this way, private finance can bend the arc of history towards climate justice, value can serve values, moral sentiments can rebalance market sentiments, and the Glasgow of COP 26 can be reunited with the Glasgow of Adam Smith.