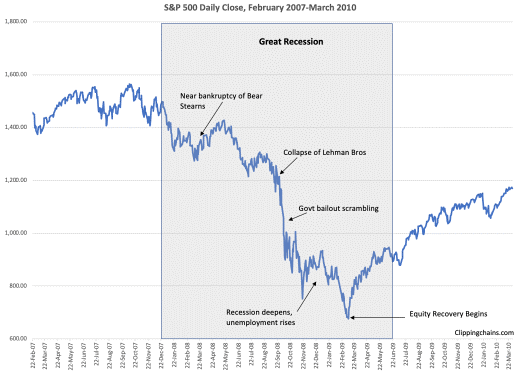

Then, starting with a couple of obscure European funds, the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression had begun. Within a year, a series of institutions, including Northern Rock and Lehman Brothers, had failed or been rescued by the State and the world economy was in freefall.

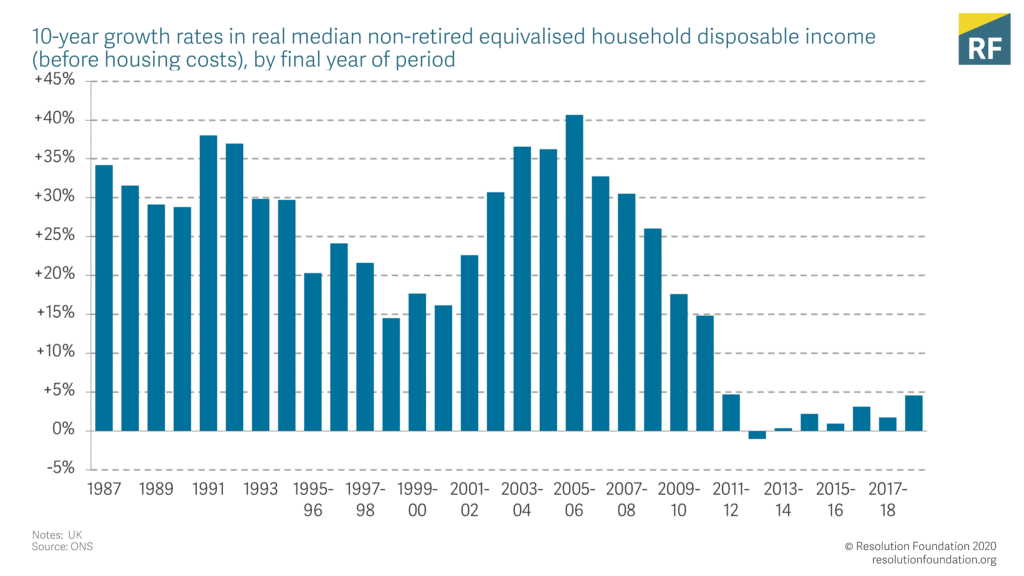

The future arrived with a bang – from Great Moderation to Great Recession, from boom to bust, from confidence to mistrust – and the consequences were severe. A lost decade. Real household incomes in the United Kingdom did not grow at all over the following 10 years.

Since then, growth in trade and capital flows has slowed sharply and the multilateral trading system has been unwinding. There has been growing mistrust of experts.

The financial system came crashing down on the heads of ordinary people, some of whom are still suffering the consequences. They, like Her Majesty, The Queen, wondered, “Why did no-one notice it?”

Most economists, financiers and policy makers missed these growing vulnerabilities because they were involved in the great project of completing the financial market universe with the precision of physicists. Economists generally suffer from physics envy. They covet its neat equations and crave its deterministic systems, and this inevitably leads to disappointment.

The economy isn’t deterministic. People aren’t always rational. Human creativity, frailty, exuberance and pessimism all contribute to economic and financial cycles.

And so it was in the run-up to the global financial crisis. The new era of thinking in the first decade of the Millennium was grounded in very real boosts to prosperity from global integration and technological innovation. Sadly, that initial success bred complacency and the infrastructure of markets didn’t keep up with innovation.

Bankers’ confidence caused them to allow their balance sheets to weaken. Few of these “masters of the universe” focused on the longer-term consequences of their actions. Market failures and human frailties were ignored. Moral sentiments turned into market sentiments.

This was not merely a technical failure. This was a crisis of values, as well as value. The pre-crisis era was an age of disembodied finance where markets grew far apart from the households and businesses they ultimately served.

Eight hundred years of economic history teaches that financial crises occur, roughly, once a decade. In finance, institutional memories are short. Lessons that are painfully learned during busts are gradually forgotten as new eras dawn and the cycle begins anew, and this is a depressing cycle of prudence, confidence, complacency, euphoria and despair.

It’s a cycle which reflects the power of the three lies of finance.

1. The first lie is the four most expensive words in the English language: “This time is different.” This misconception is usually the product of an initial success, with early progress gradually building into blind faith in a new era of effortless prosperity. Several factors drove the debt super cycle in the run-up to the financial crisis, including demographics and the stagnation of middleclass real wages, which itself was a product of technology and globalisation. Households had to borrow to increase consumption.

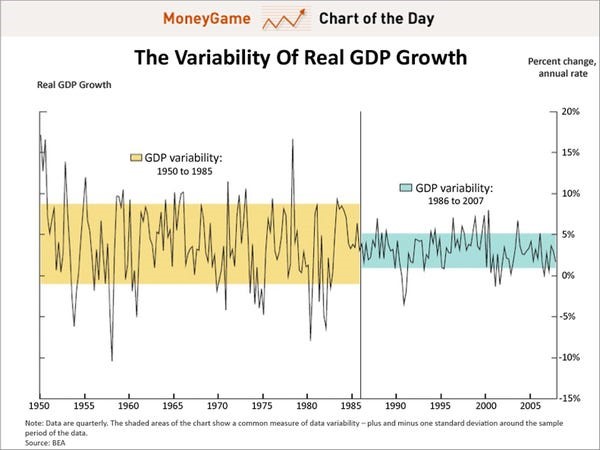

Financial innovation made that easier and the ready supply of foreign capital made it cheaper. Most importantly complacency amongst individuals and institutions, fed by a long period of macroeconomic stability and rising asset prices, made this remorseless borrowing seem sensible.A deep-seated faith in markets lay behind the new era thinking of the Great Moderation. Captured by the myth that finance can regulate and correct itself spontaneously, authorities retreated from their regulatory and supervisory responsibilities.

2. This leads to the second lie: the belief that the market is always right. This has two dangerous effects. First, the belief that if markets are efficient, we can identify bubbles or address their potential causes. Second, that markets should possess a natural stability, and any evidence to the contrary must be the product either of market distortions or incomplete markets, which can be corrected. Such thinking dominated the practical indifference of policy makers to the housing and credit booms before the crisis. Much financial innovation springs from the logic that the solution to market failures is to build new markets on old ones. Such market fundamentalism relies on people being able to calculate the odds of each and every possible scenario. A moment of introspection reveals the absurdity of these assumptions compared to the real world. More often than not, even describing the universe of possible outcomes is beyond the means of mere mortals, let alone ascribing subjective probabilities to each outcome.

The swings of sentiment that result – pessimism one moment, exuberance the next – reflect not only nature’s odds but also our assessments of those odds, and the volatility of human behaviour.

3. The third lie, that markets are moral, takes for granted the social capital that markets need to fulfil their promise. Repeated episodes of misconduct in the run-up to the global financial crisis called into question the social licence that markets need to innovate and grow. Financial market participants were found to have knowingly mis-sold to clients products that were inappropriate or even fraudulent. Traders manipulated key interest rates and foreign exchange benchmarks to support their trading positions, while costing retail and corporate clients who relied on those benchmarks billions of pounds. Even today for many people there remains a clear sense of injustice caused by the failure to hold these people adequately to account.

It is obviously vital that markets work well and that they are seen to do so.

So: this time is not different; markets are not always efficient; and we can suffer from their amorality. The question is what to do with such knowledge and how can we retain it so that financial history stops rhyming?

The answer starts with the radical programme of G20 reforms that are working to create a safer, simpler and fairer financial system. These pro-market reforms are vital, but they are not sufficient in and of themselves.

Regulation alone won’t break an eight-century cycle of financial boom and bust. To resist the siren calls of the three lies, policy makers and market participants must recognise the limits of markets and rediscover their responsibilities for the system.

If the financial and COVID crises teach us anything, it’s humility.

We cannot anticipate every risk or plan for every contingency, but we can and must plan for failure. That means creating an anti-fragile system, a system that can withstand both the risks we see and those we don’t.

An anti-fragile system requires banks that can stand on their own, which is why banks are now required to hold ten times as much capital as they did before the crisis.

An anti-fragile system requires protection against major financial institutions being “too big to fail”. Perhaps the most severe blow to public trust was the revelation that scores of banks operated in a “heads I win, tails you lose” bubble.

An anti-fragile system must also be as robust to operational failures as to financial ones. In our digital era, systemic shocks can come from nonfinancial sources, such as cyberattacks. So to improve firms’ defences, the UK’s largest banks are now subject to what are called “cyber penetration tests”.

To re-establish the social licence of finance requires a combination of regulation and true cultural change. In the long history of scandal, the potential solutions have oscillated between the extremes of light-touch regulation and total regulation, and there are problems with each of these.

More comprehensive and lasting solutions combine public regulation with private standards to restore the accountability of individuals for their own actions and for the system, and there are three components of this: aligning pay with values; increasing senior management accountability; and renewing a sense of vocation in finance.

Ultimately though, social capital is not contractual. Integrity can neither be bought, nor regulated, it must come from within and it must be grounded in values.

All market participants should recognise that market integrity is essential to fair financial capitalism.

There is a need to recognise that financial capitalism is not an end in itself but a means to promote investment, innovation, growth and prosperity.

It also means that financial employees should be grounded in strong connections to their clients and their communities.

The G20 reforms since the crisis are intended to create a stronger, simpler and fairer financial system, and with time and continued service it can regain people’s confidence.

But we must be vigilant, resist the three lies of finance and reinforce some core financial truths, because the next time won’t be different.

Markets aren’t always right and can overshoot in both directions; Central Banks need to return to their roles as lenders, not remain as buyers of last resort; and because markets aren’t inherently moral, they can distort value and corrode values if they are left unattended.

There is no simple unifying formula to break the destructive cycle of financial history. Physics won’t save finance. Promoting a system in which all its participants live society’s core values will.