So, how could this have happened?

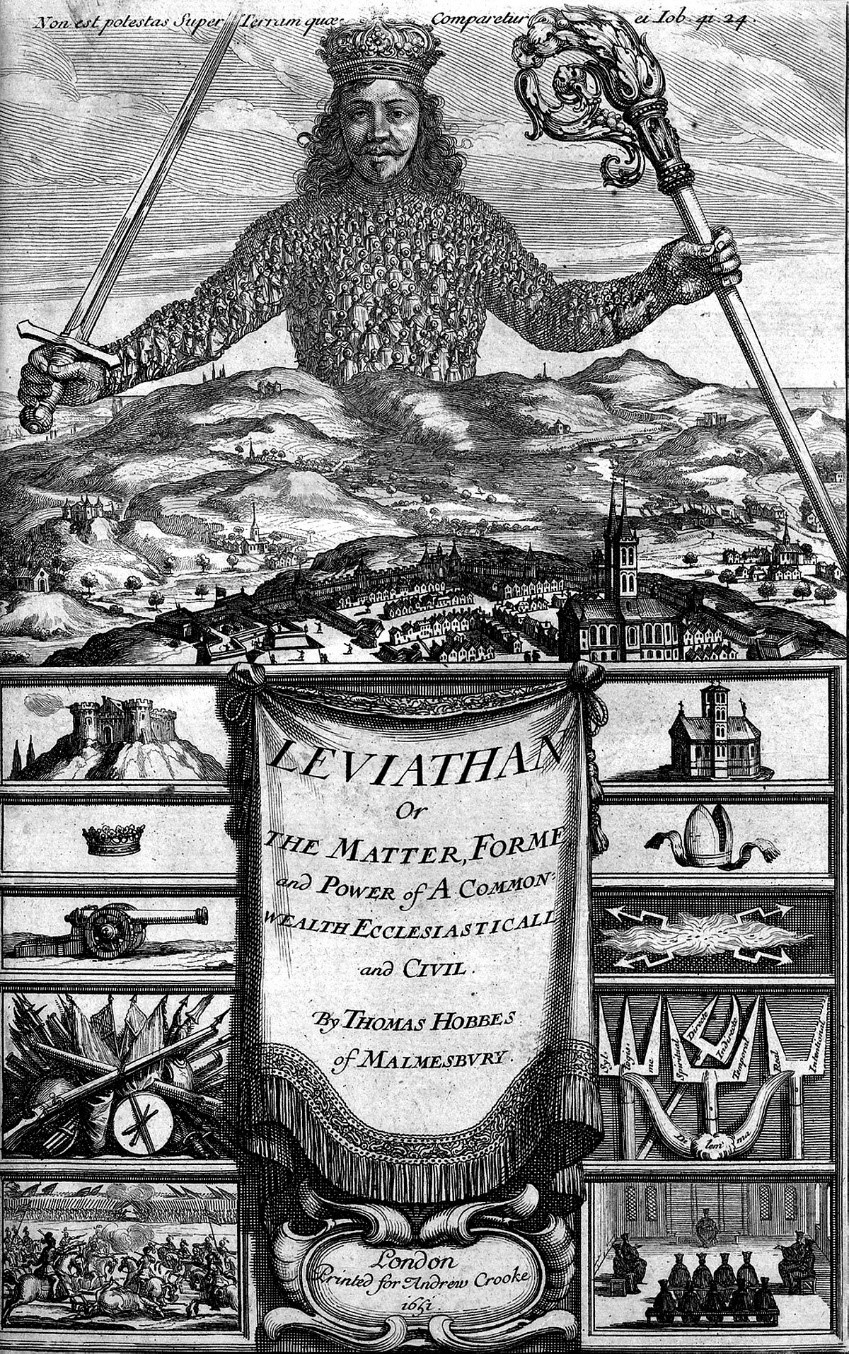

In his classic treatise, Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes described back in 1651 how the fundamental duty of the state is to protect its citizens from violence.

Over the centuries, the government’s role as protector has been extended to areas as varied as promoting financial stability, protecting the environment, maintaining data privacy, and yes, preparing for a pandemic. For some people, these are essential public goods. To others, this is the creep of the nanny state.

States failed in their duties to protect and now the COVID crisis is forcing us to confront questions of how we value health, wealth and opportunity.

Looking back at the initial response to the catastrophe, something is striking. Governments and citizens drew on their core values and made decisions based on human compassion, not financial optimisation. The economy was put on life support in order to save lives.

Governments have asserted a level of control over our everyday activities that has surpassed anything in modern history.

Staying at home during a lockdown or wearing a mask following government guidance is part of the Hobbesian bargain: obedience in exchange for protection.

Many are willing to comply with decrees of a legitimate and trusted power, but such state legitimacy must be continually earned. Compliance will be undercut if concerns develop about fairness, administrative competence or the validity of the strategic objectives themselves.

Most people across the globe have supported lockdown measures and massive government spending, even if they perceive little personal risk, and they’ve gone well beyond compliance to active charity.

This has come at great cost. Lockdowns deepen economic uncertainty, disrupt social lives, and bring about incalculable levels of stress and anxiety.

Solidarity in a pandemic is an example of positive behavioural contagion. If those around us obey lockdown rules or wear masks, we’re more likely to do so as well. This concept goes back to the moral sentiments of Adam Smith, and it reminds us that virtue is not a finite resource to be conserved, but a value that grows with use.

At the beginning of the pandemic, many said that this tragedy showed that we are all in the same storm. It quickly became apparent, however, that we were in very different boats.

COVID is fundamentally unequal in its impact and it has exposed deep inequalities in our society.

The virus particularly targets certain individuals:

If we only cared about the financial security of survivors, we’d never spend any money to save the life of retirees or those permanently out of work.

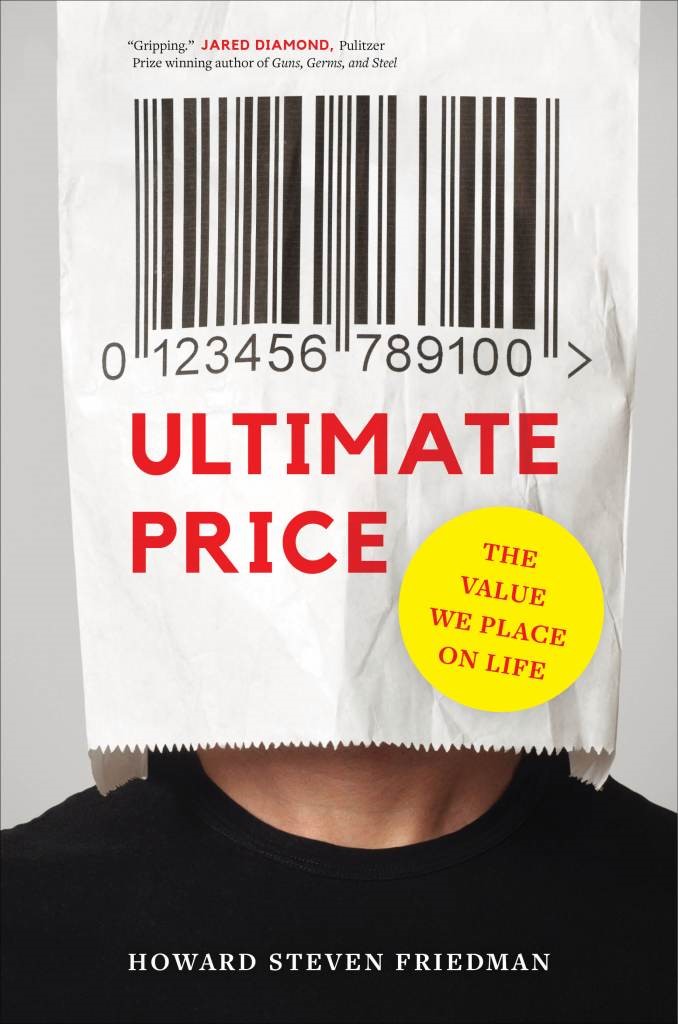

Today, public policy decisions around the world use calculations of statistical life and the related concept of quality-adjusted life year as part of what has been termed the cost benefit revolution.

The attraction of doing so is that financial values encourage clear decisions. The question is whether this clarity is justified and whether it reflects the values of society.

There are four reasons why the value of life should not be assessed by the market.

It is not clear that these issues are best answered by cost benefit analyses, flawed methodologies and hidden inequities.

We need to resist the siren call that there is a trade-off between the economy and our health. There’s extensive cross-country evidence that these objectives are complementary.

Data from various countries indicate that more than 80% of the reduction in mobility has been voluntary. The fact is, people are reluctant to go back to work or to the office or to go out to spend, when they are concerned about their health. The lesson is that we need either to control the virus or credibly lessen its impact on people’s health.

So how should we proceed? Ideally, we should define our core purpose first and then determine the most cost effective interventions to achieve this goal. Such cost effectiveness analysis explicitly seeks to achieve society’s values.

During the pandemic people have prioritised the values of solidarity, fairness and responsibility. This suggests that COVID policy should be centred on health and social outcomes, minimising the risks of death, ensuring that the sick have adequate treatment and buying time for better treatments and vaccines.

A strategic approach to COVID is the best combination of policies to achieve the desired level of infection control at minimum economic cost, with due respect for inequality, mental health and other social consequences. Calculating those costs then provides guidance when considering different containment strategies. That means paying attention to the impact on fairness, education, inter-generational equity and economic dynamism.

In deciding which sectors of the economy to open or close, policy makers must weigh up the spill overs from one activity to another. Policy makers should restrict economic activities that have weak economic contributions but high infection risks, and open or even subsidise those with low infection risks and a high and positive economic contribution.

In the same vein, fair access to healthcare is essential. If it is compromised, the bonds between the state and citizens will be undermined.

Finally, we need to spend public money wisely; it is not unlimited. This is not about a return to austerity but, rather, about more effective spending by supporting education and skills, and the productive capacity of businesses. In short, we will need, in time, to begin to move from redistribution to regeneration.

Governments undervalued resilience in the years leading up to the crisis, failing in their duty to protect their citizens. People across the world rose to the occasion, displaying their values of solidarity, fairness and responsibility, but at the same time, the COVID crisis has revealed deep strains in our society. Essential workers have been undervalued.

After decades of risk being steadily downloaded onto individuals, the bill has arrived. Entire populations are experiencing the fears of the unemployed and sensing the anxiety that comes with inadequate or inaccessible healthcare. These developments have rightly raised expectations for fairness and greater equality in all spheres of life.

In recent decades we have been moving relentlessly from a market economy to a market society. Increasingly, to be valued, an asset or activity has had to be in the market, and this crisis could help reverse that so that public values help shape private value. When pushed, societies have prioritised health first and foremost, and then looked to address the economic consequences.

In this crisis, we know we need to act as an interdependent community, not as independent individuals. The values of economic dynamism and efficiency have been joined by those of solidarity, fairness, responsibility and compassion.