Growth in e-commerce is gathering considerable momentum, with the impact of the likes of Amazon on the high street well documented. Facebook recently announced enhancements to its Instagram platform which will enable users to buy tagged products which are being advertised on the platform. This cuts out the need for customers to go onto the retailer’s website.

This new functionality, coupled with most retailers’ free returns policies, improves the convenience for the end user and arguably reduces the need for them to head into their nearest store to have a browse, or to contemplate withdrawing cash from the nearest ATM.

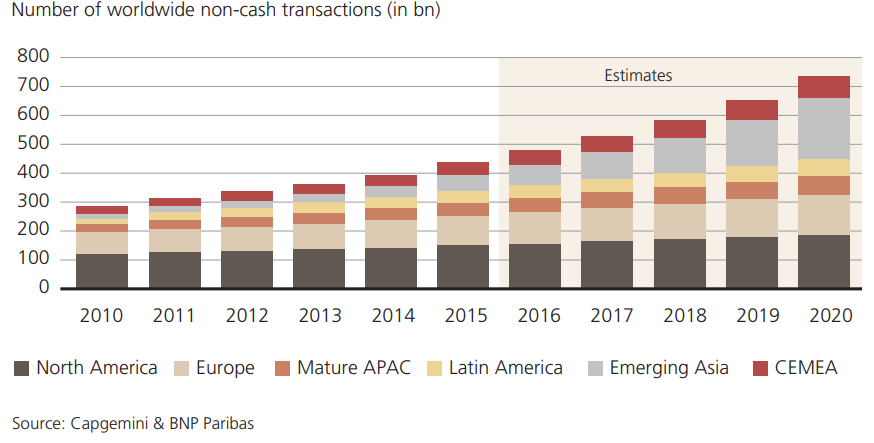

As the chart below shows, the West is not as far down the road as other countries around the world. In Asia, a cashless transition is already approaching an inflection point. Central governments are shaping their policies in favour of a cashless society while technological innovation, high smart phone penetration, and structural factors like demographics and urbanization are driving adoption.

The South Korean Central Bank has been promoting the concept of a cashless society and plans to cease minting coins by 2020, while the Indian government decided to press ahead with demonetization and withdrew the INR 500 and INR 1000 bank notes. At the consumer level, during last year’s Chinese New Year, 688 million people used WeChat to send and receive virtual hongbao (traditional red packets used to gift cash). (Source: UBS, Shifting Asia: The road to cashless societies April 2018)

For many people these innovations will be useful new tools, which they then take for granted. But the suggestion in the report is that there are 25 million people in the UK for whom living in a cashless society would present real challenges.

The lack of high-speed internet infrastructure in remote and rural areas means that many merchants and retailers are still unable to use electronic payments. The Financial Conduct Authority states that there are 4.1 million adults in the UK who are in financial difficulty, and debt charities advise people to cut up cards and use only cash to assist them with budgeting.

According to the Access to Cash report, to keep the cash infrastructure of the UK operational in its current form costs £5 billion per year, much of which is fixed and paid for by high street banks. As cash use declines, the economics of this model is becoming seriously challenged, forcing banks and ATM service providers either to reduce the number of free ATMs or to get rid of them completely.

Innovation is creating a self-fulfilling cycle. Banks’ profits are under pressure and so they funnel their customers towards their cheaper, more efficient, digital offerings; branches and ATMs are then used less, and so justify cost cutting measures, as it is reflects what their customers are doing. Coupled with the threat posed by the global technology giants’ own fintech offerings, the response from banks is to invest more in their digital offerings and to continue to move away from traditional branch and ATM services.

This may be good for banks’ profits, but it does little to enhance their reputations among the public, especially those who are financially vulnerable.

(Source: Access to Cash Report – https://www.accesstocash.org.uk/media/1087/final-report-final-web.pdf)